How to Invest During the Fed’s Game of Inflation Catch-up

| By Cecilia Caminos | 0 Comentarios

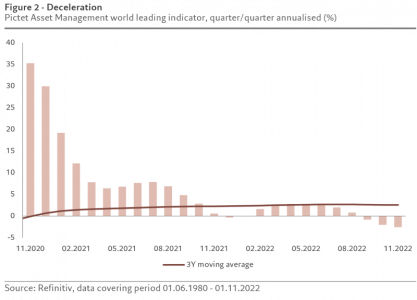

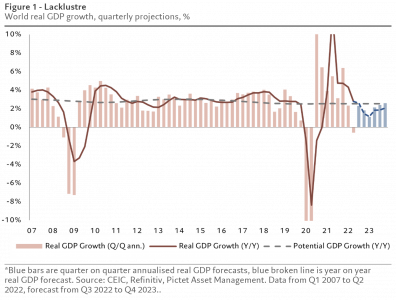

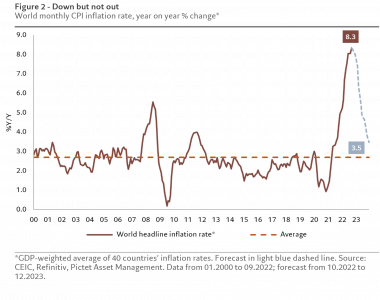

For quite some time, our team has contended that goods inflation is indeed transitory. While a slowdown has taken longer than we originally thought, goods inflation is indeed falling. However, the Fed’s chicken-and-egg dynamic of inflation first before rate hikes has them playing catch-up quite aggressively. Other than the recent bank failures, the headline-grabbing data points over the past few months are mostly encouraging and now tell a story of retreating inflation. Although CPI slowed from 9.1% year-over-year in July to 6.4% year-over-year in January, the Fed still needs to keep its foot firmly on the brake.

Slowing inflation is just one part of the equation. While the Fed’s success may allow them to moderate the pace of interest rate hikes or eventually hold rates at a high level, Chairman Powell and the rest of the Fed must also work to restore credibility. In fact, Chairman Powell reiterated his message that inflation remains a way off from where they need to see it and there is more work to do, even as the Fed slowed its tightening pace in February.

Inflation peaked last year in July. Since then, we’ve experienced a slow and steady decline in the headline number. We’ve also seen services inflation taking an increasing share of the price pressures and goods inflation taking a decreasing share. As I have argued, this is important in terms of the Fed’s third mandate, which I believe will determine the timing of the central bank’s pivot. If services inflation remains above two percent, though lower than where we see today, and goods inflation keeps shrinking, the Fed may tolerate core inflation above 2%. Given that services inflation is heavily driven by rising wages, and today, much of this increase is focused on the lower-income population, the Fed views this as ‘good’ inflation. For some time, I have argued that the Fed’s third mandate is one of social stability, or more succinctly, compressing the wage gap.

Chair Powell and the Fed’s race to cross the 2% inflation finish line is made more difficult by the strong US economy headwinds blowing in their faces. Imagine also trying to do this while wading through a flood of government spending stemming from December’s omnibus spending bill. In other words, this battle against inflation is at odds with the easy fiscal policy crosscurrents. Unsurprisingly, I think it will be more difficult for the Fed to go from 6% to 2% inflation than it was to shed the excesses from 9% to 6%.

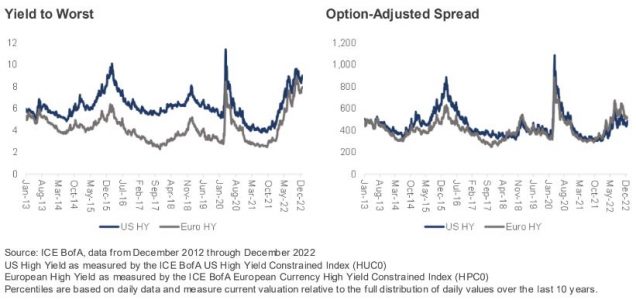

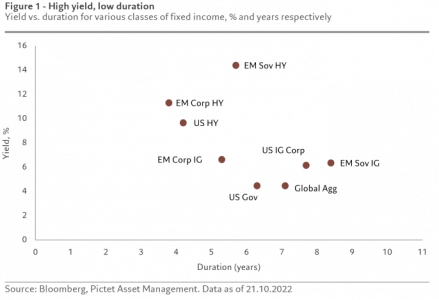

The silver lining to all of this is that a tightening Fed means that yield and income are back! Investing in T-bills or two-year treasuries will not provide a better economic outcome than investing in areas in which investors can earn a credit risk premium. For a while now we have suggested that the economy will be more able to perform into higher rates. However, we have also said that our belief is that there is such thing as rates too high to sustain growth. We think that about 3.75% is fair value for the 10-year treasury, and we are opportunistically adding protection with treasuries when rates rise above this level and reducing duration when we have seen rates notably below this level. We work to balance the opportunity in both credit and rates and expect that volatility will remain high throughout the year.

Away from rates, all the talk about an imminent recession has pushed spreads further above treasuries in most areas of the market. Given the ongoing strength in consumer spending, we believe the best relative value on a sector level continues to be in securitized debt. These non-agency, asset-backed securities spreads on the AA to BBB ratings spectrum are wider than investment grade corporates.

Although this is generally the case, today’s premiums are wider than usual. We favor ABS and residential mortgage-backed securitized credits, which provide additional protection in the form of fast paydown and underlying collateral to provide some ballast when—not if—we enter a recessionary environment.

We prefer prime borrowers through bonds backed by consumer loans and autos because subprime customers are much more sensitive to evaporating stimulus and heightened inflation. When we elect to take on subprime exposure, it’s because we believe the bonds are “senior” in the capital structure and these bonds tend to pay down very quickly.

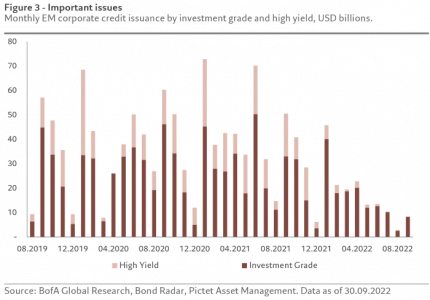

Many investors also ask about emerging market debt. We are cautious and selective in these spots given their inherent high levels of global risk. But slowing U.S. growth means EM growth differentials are more favorable in 2023 and an eventual pivot from the Fed will slow the rise of the dollar.

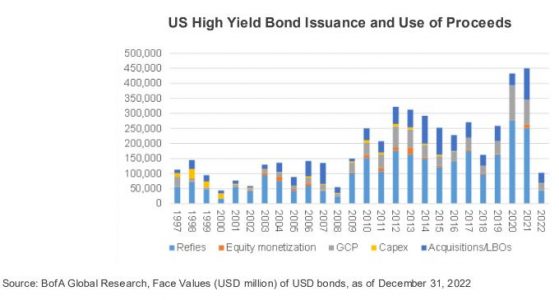

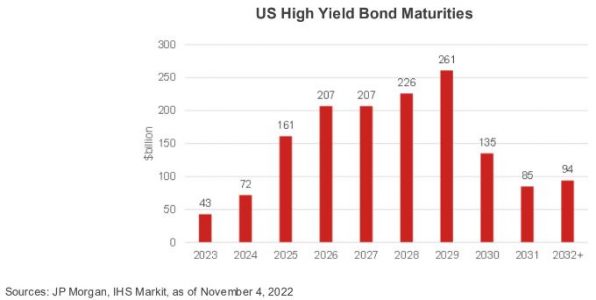

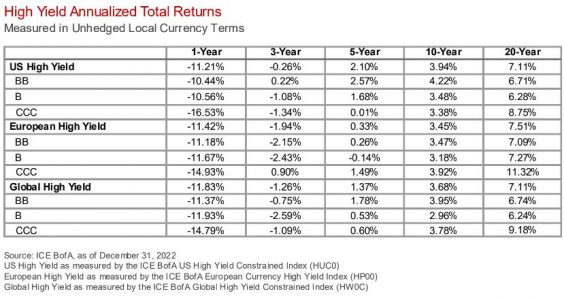

In terms of credit quality, we favor investment-grade corporate bonds over high-yield corporates. In an environment of weak growth, we are weighted toward non-cyclical names in utilities, healthcare, select tech, and high-quality financials. We won’t close the door entirely on high yield—seven to eight percent would capture any investor’s attention¬—but as with emerging markets, we pair our robust bottom-up, fundamental process with a top-down view to be highly selective in our approach.

Looking ahead, we still see some red lights on the dashboard. Few investors have weathered an inflationary storm like this, and the inflationary environment last time was radically different. The last decade’s game of monetary and fiscal stimulus has had profound effects on the global economy, and without a playbook, it’s hard to predict how this experiment may end. Caution is the only rule, and we believe we are positioned well to capture yield and remain defensive.

Tribune by Jeff Klingelhofer, CFA, is Managing Director and Co-Head of Investments at Thornburg Investment Management.