Three major central banks held their October meetings, highlighting the divergence in their monetary policy approaches. David Kohl, Chief Economist at Julius Baer, succinctly summarizes the situation: “The Federal Reserve maintains a restrictive policy stance but is expected to ease due to signs of labor market weakness; the ECB sees limited need to act, as inflation is within target and growth risks are not particularly severe; and the Bank of Japan continues its accommodative policy, despite inflation being above target.”

A similar view is offered by Salvatore Bruno, Deputy CIO and Head of Active Management at Generali AM (part of Generali Investments). He focuses on the risk of the Federal Reserve losing its independence: the fiscal expansion promised by the Trump Administration requires low interest rates to limit the cost of debt interest payments, which already exceed 10% of fiscal revenues. This has created strong pressure on the Fed from the administration to resume the rate-cutting cycle. “It won’t be easy to resolve the conflict between the White House and the Fed before the expected change of the central bank’s chair in mid-2026. Nonetheless, there seems to be room for further rate cuts, though possibly fewer than the market expects,” the expert notes.

Regarding the ECB, Bruno sees a different scenario. The market does not anticipate further cuts, as inflation is expected to stabilize and growth prospects appear to have improved. He explains that investors will need to evaluate planned fiscal expansion — especially in Germany — and the potential spillover effects of French political tensions on local interest rates.

A Cinematic Take on Monetary Policy

José Manuel Marín Cebrián, economist and founder of Fortuna SFP, analyzes the current divergence among central banks through a cinematic lens, drawing on the film The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, starring Clint Eastwood.

In his view, the “good” is the ECB and its “monetary siesta”: Christine Lagarde, like a sheriff who has already cleaned up the town, has decided to let the dust settle. With CPI at 2.2%, she feels the job is done. No more cuts, no bailouts, no surprises. Rates stay where they are, and the message is clear: “We’ve done enough — now let others manage.” Meanwhile, the euro fans itself in the sun, the Frankfurt hawks toast with Riesling, and investors breathe easy (for now). The ECB appears disciplined, calm, and with a cool trigger finger. But like any desert hero, it could discover that danger also lurks in calm… especially if European growth gets stuck halfway between the desert and the saloon.

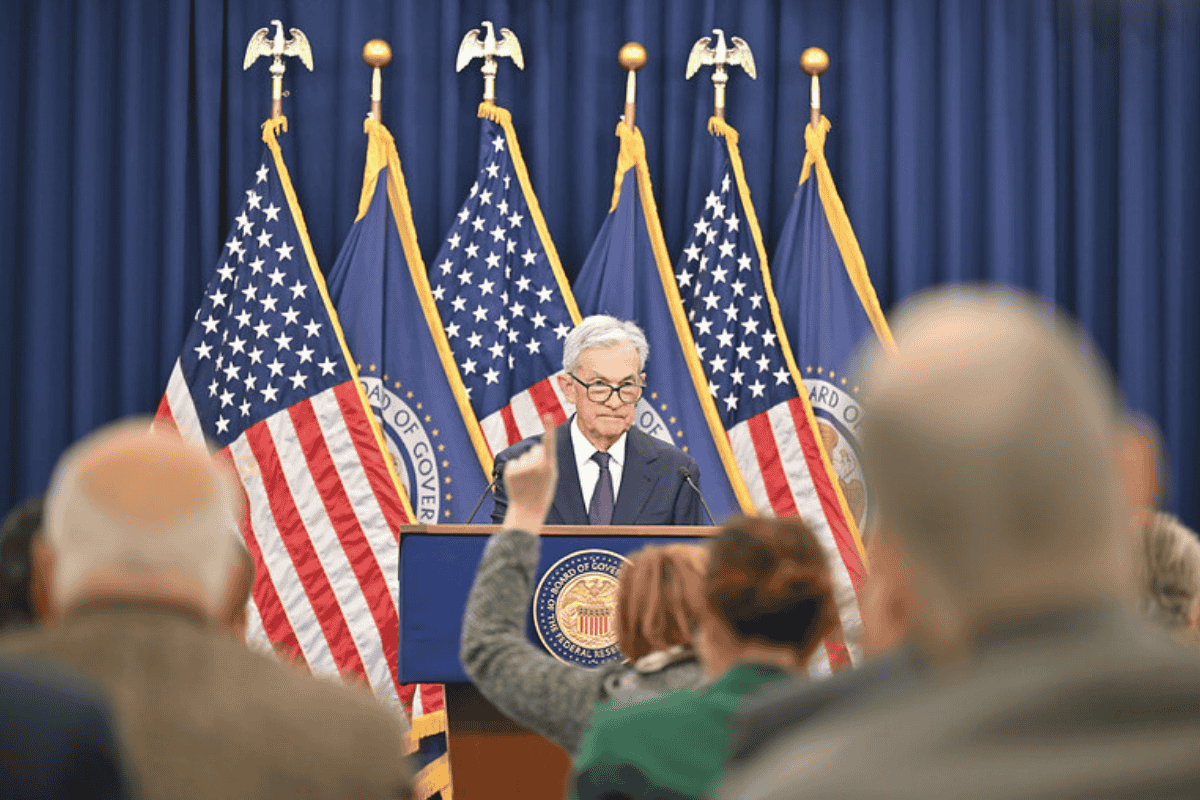

The role of the “ugly” goes to the Fed and its “dance with Trump”: Jerome Powell faces a tougher role. In his personal duel, he battles three foes — inflation, the labor market, and Donald Trump. Inflation has settled at 3%, employment is starting to show signs of weakness, and political pressure from Mar-a-Lago echoes even in the Fed’s hallways. The result is a script full of dilemmas. Powell promises two rate cuts for 2025 and four or five for 2026, trying to please everyone. But markets already suspect this dovish feeling could end in tragedy if inflation returns to the dance. Powell, sweating under his hat, keeps calm as he counts his rounds: each cut must be precise, or the dollar sheriff may lose control of the town.

Finally, Marín Cebrián casts the “bad” as the Bank of Japan and its “rusty revolver”: the eternal misunderstood villain. After decades of firing negative rates, it now seems ready for the unthinkable — raising them. The yen, once feared by none, is now moving like a runaway outlaw, and markets wonder if the BoJ will finally deliver justice to its inflation. The dilemma is classic: raise rates too fast and kill growth; don’t raise them, and the yen bleeds. The result is a Kurosawa-style script, with Zen economics, meticulous decisions, and a lead character who only fires after meditating for three days straight.

Marín Cebrián describes the final showdown in monetary terms: the good (ECB), the ugly (Fed), and the bad (BoJ) stand at the crossroads of the global economy. Lagarde watches calmly, Powell tries to keep his composure, and Ueda sharpens his monetary katana. “As always, the markets place their bets and wait for the first shot. Because in the global economy, the winner isn’t the fastest… but the one who holds their ground,” the expert concludes.

Federal Reserve

Following the latest rate cut in October, responses from financial firms have continued. Guilhem Savry, Head of Macro and Dynamic Allocation Strategy at Edmond de Rothschild Private Banking, sees long-term U.S. interest rates likely remaining higher than previously forecast. However, the end of quantitative tightening, he says, is a reason to support short-term bonds, while the Fed is likely to resume purchasing Treasury bills.

He notes significant disagreement within the FOMC, with some members citing the lack of official data as a compelling reason to avoid another rate cut in December. This divergence and the uncertainty around the Fed’s next chair “could complicate further rate cuts in the coming months,” though the expert still believes a December cut is likely, which should continue to support equity markets and U.S. government debt.

European Central Bank

Konstantin Veit, portfolio manager at Pimco, believes that after the ECB’s decision to hold rates steady, there is little justification for further monetary adjustments. He considers the 2% interest rate “a level likely seen as the midpoint of a neutral range by most Governing Council members.” He adds that Pimco tends to agree with the prevailing view within the ECB that medium-term inflation risks remain broadly balanced. Given the ECB’s reaction function is not geared toward fine-tuning, he still expects “a prolonged period of interest rate inaction.”

Sandra Rhouma, Vice President and European Economist on the Fixed Income team at AllianceBernstein, still anticipates a cut in December, but given the ECB’s latest stance and recent data, “the bar is now higher than it was a few months ago.”

Bank of Japan

The Bank of Japan also held rates steady, offering no surprises, according to Sree Kochugovindan, Senior Research Economist at Aberdeen Investments. The expert notes the overall tone of the press conference was dovish: spring wage negotiations remain the cornerstone of monetary policy direction, and Governor Kazuo Ueda expressed concern that sectors affected by tariffs — such as manufacturing — may struggle to raise wages.

Amid doubts over its independence, Ueda made clear that the BoJ will act in line with its mandate, not under political pressure. Even Prime Minister Takaichi reiterated the Bank of Japan Act, which legally enshrines the institution’s independence.

Kochugovindan maintains his view that the bank will wait at least until January to raise rates by 25 basis points, to 0.75%. “Beyond that, we see a very gradual pace of hikes, as the Bank of Japan will wait for domestically driven core inflation to accelerate,” he concludes.