There are just four days left before the tariffs imposed by the U.S. come into effect for countries that have not reached a deal. The most recent to do so are the European Union, which has secured a provisional trade agreement under which most of its exports to the U.S. market will be subject to a 15% tariff, and Japan, which agreed to a flat 15% tariff on all its products. Beginning August 1, however, imports from Canada, Brazil, South Korea, Cambodia, and Bangladesh will face tariffs ranging from 25% to 50%.

Experts expect further announcements in the coming days—particularly regarding the preliminary agreement with China, and the ongoing negotiations with India, which have made progress but remain unresolved. Additionally, Mexico, Brazil, Canada, and South Korea still lack comprehensive agreements and may face further tariffs if negotiations don’t conclude soon.

On the recent deals with the EU and Japan, Philippe Waechter, Chief Economist at Ostrum AM, believes both were fighting the same battle: “The tariff is identical (15%), the exception on steel and aluminum remains at 50%, the market opens further to American companies, and Europe commits to investing $600 billion. Japan agreed to $550 million. So far, we don’t have the details on how the investment benefits will be distributed (in Japan’s case, 90% goes to the U.S.). Europeans will also purchase $750 billion worth of energy over the next three years, moving away from climate targets, and will spend heavily on American military equipment.”

According to Waechter, the EU and Japan agreements show that “to remain dependent on the U.S. market, Europeans and Japanese are willing to pay an exorbitant price, justified only by the risk of isolation.” He adds that these tariffs reflect a global cycle long dominated by U.S. consumers. “Once that situation consolidated, increased tariffs began trapping the rest of the world, which now must pay to maintain cyclical momentum.”

Jared Franz, economist at Capital Group, stresses that not all trade barriers are created equal. In this case, he argues that Trump is using tariffs for multiple purposes—the clearest being negotiation. “The U.S. president has made it clear that some tariffs are meant to pressure countries into helping the U.S. meet its political goals, such as fighting illegal immigration and curbing drug trafficking. These may be temporary,” he notes. In contrast, the cases of Europe, Japan, and Mexico are more about rebalancing. “Reciprocal tariffs are aimed at restoring balance with other trading partners and primarily reducing the U.S. trade deficit,” Franz adds.

He concludes, “These motives will heavily influence the long-term tariff landscape. Tariffs used for negotiation will likely be short-lived, while those tied to broader strategic goals could be more permanent.”

One More Agreement, Less Uncertainty

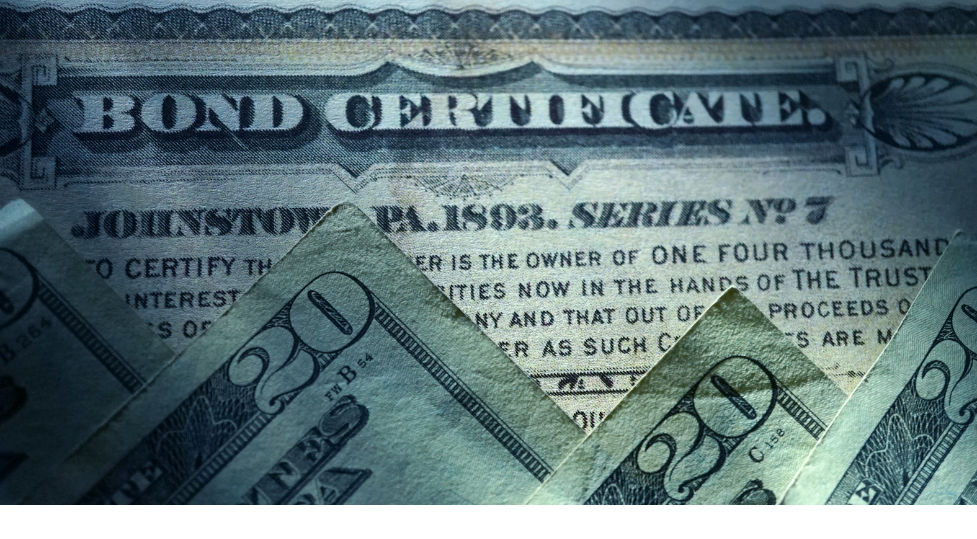

The terms of the EU–U.S. trade deal include a base tariff of 15% on nearly all EU imports, including key sectors like automobiles (currently taxed at 27.5%). Tariffs on EU steel and aluminum remain at 50% for now, though a quota system may replace them. The agreement also involves major spending commitments: the EU will purchase $750 billion worth of oil, gas, nuclear fuel, military equipment, and semiconductors during Trump’s second term. Meanwhile, European companies are expected to invest $600 billion in the U.S. during the same period.

So far, European equity markets have responded with optimism, as the deal reduces uncertainty. “There’s progress in trade negotiations, but risks remain. Investors are closely watching economic data for signals on tariff impacts and potential policy decisions. With tariff talks ongoing and global monetary policy at a turning point, the coming weeks could be pivotal for shaping investor expectations for the rest of 2025,” say analysts at Muzinich & Co.

From a European perspective, another positive factor is that EU goods are now on equal footing with those from similarly developed competitors like Japan and may receive better treatment than many emerging markets that have signed deals with the U.S. in recent weeks. However, if market optimism drives the euro higher, that could become a headwind for the eurozone, warns Gilles Moëc, Chief Economist at AXA IM.

Avoiding the Worst-Case Scenario

According to Apolline Menut, economist at Carmignac, the agreement prevents the worst-case scenario: Trump’s threatened 30% tariffs, chaotic retaliation, and a full-blown trade war. “Europe lacks the strategic economic and technological leverage that China holds over key industrial supply chains. True, U.S. manufacturers rely more on European suppliers of intermediate goods than vice versa, but in an escalating retaliation cycle, Trump could have expanded the fight to include restrictions on energy and digital services—areas where the EU is fully dependent on the U.S.,” she says.

What the EU Loses

Still, Waechter calls it “a sad day” for Europe: “Europe is so afraid of being isolated from the U.S. that the negotiations focused only on goods—not on the broader spectrum of goods and services, which are more balanced in trade terms. This means Europe has forfeited the chance to pursue technological independence. The imbalance in services is largely due to technology. Draghi’s hope of massive investment to close the tech gap with the U.S. is now just a dream. The ability to generate a strong income dynamic has proven a mirage. Income distribution will become a real power struggle within Europe, as the pie won’t grow significantly. It will have to be split among the active and inactive, and even among the active. Social dynamics will be interesting—but also very dangerous.”

Analysts at Ebury acknowledge the negative economic impact but note that greater harm was avoided: “While many details of the agreement still need to be finalized—and tariffs will likely continue to weigh meaningfully on growth—investors are relieved that the worst-case scenario has been averted.”

Felipe Villarroel, portfolio manager at TwentyFour (Vontobel), sees similarities with the deal struck by the U.K.: “This is a suboptimal outcome for the U.S., the EU, and the global economy—but it’s one the economy can likely withstand without catastrophic macro consequences. Experts have already priced in a 10–15% tariff rate. Markets have had time to absorb what this result means for businesses and growth projections. The conclusion seems to be that certain sectors, such as autos, will take a hard hit, while others will suffer indirectly through slower growth—but can keep going,” he says.

European Equities in Focus

On a more positive note, Villarroel highlights that Europe managed to shield some key sectors from harsher tariffs (ranging from 25% to 50% or more): “The agreement lowers auto tariffs (from the 25% under ‘Section 232’ to 15%) and covers both semiconductors (threatened with a 25% tariff due to a pending BIS investigation) and pharmaceuticals (for which Trump floated potential tariffs of up to 200%). It significantly reduces trade policy uncertainty for European supply chains—though the devil is in the details, especially around ambiguous zero-for-zero tariff provisions.”

Lastly, Johanna Kyrklund, Group Chief Investment Officer at Schroders, continues to emphasize that Europe benefits from global investors’ search for diversification in equity portfolios. “We’ve seen strong demand for European assets—both equities and bonds. European stocks have performed well this year, and we still see value. So, I believe Europe has been the main beneficiary of global investors’ diversification push. There’s also been significant interest in European bonds, showing that investors aren’t cutting exposure but diversifying. Meanwhile, the euro has strengthened against the dollar. In fact, we believe there’s still upside in the euro and remain quite positive on European markets,” Kyrklund concludes.